ナショナルバイアスが強いとされるジャッジ一覧

Figure Skating Judging Reviewでは、データベースに乗せられている177人のジャッジについてナショナルバイアスがあるかどうかを調べています。そして、統計的に検討して明らかにナショナルバイアスが働いているジャッジ92名を特定しました。

※詳しいレポートの内容については、別ページの「Judging Bias and Figure Skating: Part One – Nationalistic Bias」及び【翻訳版】フィギュアスケートの採点調査第一

部」をご覧ください。

ここでは、その内容をもとに、ナショナルバイアスを強く示すジャッジを一覧表にまとめました。

一番右の欄の印は、平均スコアから離れた点数を付ける傾向が強い順に◎>●>△と示しています。つまり◎は●より悪質度が高いと言えます。

また、右から2番目の欄は、Buzz Feed Newsが行った調査で、2018オリンピックに参加するジャッジの中で明らかにナショナルバイアスが見られた人物として挙げられている場合◎をつけています。

二重に◎や●がついている場合は、確実にナショナルバイアスの働いた採点を行っているジャッジであると言えると思います。

今後試合を見る際の参考になれば幸いです。

ナショナルバイアスが見られるジャッジ |

||||

| 1 | Nicole Leblanc-Richard | カナダ | ◎ | ◎ |

| 2 | Anna Kantor | イスラエル | ◎ | ◎ |

| 3 | Maira Abasova | ロシア | ◎ | ◎ |

| 4 | Elena Fomina | ロシア | ◎ | ◎ |

| 5 | Olga Kozhemyakina | ロシア | ◎ | ◎ |

| 6 | Sharon Rogers | USA | ◎ | ◎ |

| 7 | Walter Toigo | イタリア | ◎ | ● |

| 8 | Yuriy Guskov | カザフスタン | ◎ | ● |

| 9 | Adrienn Schadenbuer | オーストリア | ◎ | |

| 10 | Andre-Marc Allain | カナダ | ◎ | |

| 11 | Leanne Caron | カナダ | ◎ | |

| 12 | Reaghan Fawcett | カナダ | ◎ | |

| 13 | Jezabel Dabouis | フランス | ◎ | |

| 14 | Elisabeth Louesdon | フランス | ◎ | |

| 15 | Nicholas Russell | 英国 | ◎ | |

| 16 | Salome Chigogidze | ジョージア | ◎ | |

| 17 | Christian Baumann | ドイツ | ◎ | |

| 18 | Claudia Stahnke | ドイツ | ◎ | |

| 19 | Ekaterina Zabolotnaya | ドイツ | ◎ | |

| 20 | Albert Zaydman | イスラエル | ◎ | |

| 21 | Metteo Bonfa | イタリア | ◎ | |

| 22 | Isabella Micheli | イタリア | ◎ | |

| 23 | Miriam Palange | イタリア | ◎ | |

| 24 | Akiko Kobayasi | 日本 | ◎ | |

| 25 | Sakae Yamamoto | 日本 | ◎ | |

| 26 | Laimute Krauziene | リトアニア | ◎ | |

| 27 | Malgorzata Sobkow | ポーランド | ◎ | |

| 28 | Julia Andreeva | ロシア | ◎ | |

| 29 | Sviatoslav Babenko | ロシア | ◎ | |

| 30 | Igo rDolgushin | ロシア | ◎ | |

| 31 | Maria Gribonosova-Grebneva | ロシア | ◎ | |

| 32 | TatianaSharkina | ロシア | ◎ | |

| 33 | Alla Shekovtsova | ロシア | ◎ | |

| 34 | Bettina Meier | スイス | ◎ | |

| 35 | Yury Baulkov | ウクライナ | ◎ | |

| 36 | Anastassiya Makarova | ウクライナ | ◎ | |

| 37 | Samuel Auxier | USA | ◎ | |

| 38 | Richard Dalley | USA | ◎ | |

| 39 | Janis Engel | USA | ◎ | |

| 40 | Kathleen Harmon | USA | ◎ | |

| 41 | Taffy Holliday | USA | ◎ | |

| 42 | Laurie Johnson | USA | ◎ | |

| 43 | Cynthia Benson | カナダ | ● | |

| 44 | Karen Howard | カナダ | ● | |

| 45 | Leslie Keen | カナダ | ● | |

| 46 | Erica Topolski | カナダ | ● | |

| 47 | Shi Wei | 中国 | ● | |

| 48 | Fan Yang | 中国 | ● | |

| 49 | David Munoz | スペイン | ● | |

| 50 | Virpi Kunnas-Helminen | フィンランド | ● | |

| 51 | Ronald Beau | フランス | ● | |

| 52 | Philippe Meriguet | フランス | ● | |

| 53 | David Molina | フランス | ● | |

| 54 | Florence Vuylsteker | フランス | ● | |

| 55 | Christopher Buchanan | 英国 | ● | |

| 56 | Stephen Fernandez | 英国 | ● | |

| 57 | Sarah Hanrahan | 英国 | ● | |

| 58 | Elke Treits | ドイツ | ● | |

| 59 | Attila Soos | ハンガリー | ● | |

| 60 | Gyula Szombathelyi | ハンガリー | ● | |

| 61 | Rosslla Ceccattini | イタリア | ● | |

| 62 | Raffaella Locatelli | イタリア | ● | |

| 63 | Tomoe Fukudome | 日本 | ● | |

| 64 | Nobuhiko Yoshioka | 日本 | ● | |

| 65 | Nadezhda Paretskaia | カザフスタン | ● | |

| 66 | Sung-hee Koh | 韓国 | ● | |

| 67 | Agita Abele | ラトビア | ● | |

| 68 | Sasha Martinez | メキシコ | ● | |

| 69 | Malgorzata Grajcar | ポーランド | ● | |

| 70 | Natalia Kitaeva | ロシア | ● | |

| 71 | Lolita Labunskaiya | ロシア | ● | |

| 72 | Inger Andersson | スウェーデン | ● | |

| 73 | Hal Marron | USA | ● | |

| 74 | Jhon Millier | USA | ● | |

| 75 | Patty Klein | カナダ | △ | |

| 76 | Dan Fang | 中国 | △ | |

| 77 | Frantisek Baudys | チェコ共和国 | △ | |

| 78 | Jana Baudysova | チェコ共和国 | △ | |

| 79 | Merja Kosonen | フィンランド | △ | |

| 80 | Leo Lenkola | フィンランド | △ | |

| 81 | Ulla Faig | ドイツ | △ | |

| 82 | Ulla Limpert | ドイツ | △ | |

| 83 | Tiziana Miorini | イタリア | △ | |

| 84 | Miwako Ando | 日本 | △ | |

| 85 | Ritsuko Horiuchi | 日本 | △ | |

| 86 | Takeo Kuno | 日本 | △ | |

| 87 |

Kaoru Takino |

日本 | △ | |

| 88 | Jung Sue Lee | 韓国 | △ | |

| 89 | Igol Obraztsov | ロシア | △ | |

| 90 | Kristina Houwing | スウェーデン | △ | |

| 91 | Jennifer Mast | USA | △ | |

| 92 | Kevin Rosenstein | USA | △ | |

オリンピックのジャッジ問題について スキージャンプとフィギュアスケート(2014年の記事)

自動翻訳(原文は下にあります)

スキージャンプがオリンピックの判定を正しくする方法(およびフィギュア スケートが間違って いる方法)

判断されたスポーツでは、ある程度の偏りはおそらく避けられません。問題は、スポーツがそれを制御するために何かできるかということです。他の点では真面目なアカデミックエコノミストとして、私はオリンピックジャッジに興味を持ちました。人々のグループがどのように決定を下すかについて興味があったからです。金メダリストを選ぶ裁判官のグループは、少なくとも誰を雇うかを決定する委員会に少し似ています。個々のメンバーはそれぞれ決定について独自の意見を持ち、これらの意見は貴重な情報とメンバーのバイアスの両方を反映しています。問題は、これらの意見をどのように組み合わせ、どのようにしてメンバーが可能な限り偏見のないインセンティブを作成するかです。スキージャンプとフィギュアスケートの両方に、国家主義的な判断バイアスがあり、裁判官は自国の選手に高いスコアを与えます。しかし、スポーツはこれに対処するために非常に異なるアプローチを取ります。スキージャンプでは、国際連盟がオリンピックなどの競技会の審査員を選択しますが、バイアスの最も少ない審査員を選択していることがわかります。フィギュアスケートでは、その全国連盟が裁判官を選択することができます。

これにより、審査員にさまざまなインセンティブが与えられます。スキージャンプジャッジは、下位レベルの競技ではナショナリズムをあまり示しません。オリンピックを判断するチャンスを逃さないために、重要性の低いコンテストでナショナリズムを包み込みます。フィギュアスケートの審査員は、実際には少ないコンテストでより偏っています。彼らは実際に彼らの連合からの圧力のためになりたいと思うよりもより偏っているかもしれません。

ナショナリズム的に偏っているにもかかわらず、スキージャンプの審査員は公平性に関心があるようです。同胞の裁判官を持つことは、実際にはスキージャンプの利点ではありません。同胞からより高いスコアを獲得している間、他の4人の審査員はあなたのスコアをこれまでよりもわずかに下げ、あなたをより良い(または悪い)オフにすることはありません。逆は、フィギュアスケートで発生します。同胞のジャッジがいるフィギュアスケーターは、そのジャッジからより高いスコアを獲得するだけでなく、他のジャッジからも平均してより高いスコアを獲得します(パネルに表示されていないイベントと比較して)。これは、1998年、2002年のオリンピックで発生した投票取引の証拠です。また、伝えられるところによれば、2014年に行われています。スケーターは、他のイベントのパネルに同胞審査員を配置することからも恩恵を受けます。

スポーツの機能不全は、2002年の審査スキャンダルにどのように反応したかによっても明らかになります。国際スケート連盟は、審判団の規模を拡大する(少なくとも一時的に)、採点システムをより客観的にするなど、いくつかの賢明な改革を行いました(一部の人は行き過ぎだと考えていますが)。しかし、彼らの反応の大部分は、偏見の証拠を隠すことで構成されていました。ISUは、どのジャッジがどのスコアを与えたかを明らかにすることをやめ、競合他社やファンがジャッジメントが公正であるかどうかを確認することをより困難にしました。ISU は以前の競技会のオンラインスコアシートを変更し、どの裁判官がどのスコアを与え、各裁判官がどの国を代表するかさえわかりにくくしました。彼らは12人の裁判官の3人からスコアをランダムに落とし始めました。統計学者なら誰でもわかるように、12個のスコアのうち9個の平均は、本質的に12個のスコアの平均に乱数を加えたものです。イェール統計学教授のジェイ・エマーソンが、ある場合にはこのランダム性がメダルを獲得した人を変えたことに気づいたとき、ISUはスコアシートで報告された順序をスクランブルすることで応答したようです。この変更の唯一のもっともらしい目的は、ランダム性が結果に影響を与えたケースを特定するのを難しくすることでした。これらはすべて、問題を解決するのではなく、問題を隠すことに重点が置かれていることを示唆しています。

過去のスコアシートのスクラビングとランダム化は弁護するのが非常に困難ですが、ISUは、裁判官の匿名性は、裁判官が秘密裏にそれらを簡単に破棄できるようにすることで、実際に投票取引の防止に役立つと主張しています。この議論は、選挙での秘密投票や議会での音声投票でも基本的に同じであり、そこでは外部の影響から有権者や議員を保護することを目的としています。ただし、匿名性は、部外者による監視から裁判官を保護します。匿名性が導入された後、判断バイアスが約20%大きくなったことがわかります。この場合、透明性がより良いアプローチであることを示唆しています。

これらすべての結果の中で、私はスキージャンプの審査員が互いの偏りを取り消すことと、フィギュアスケートの審査員がそれらを強化することとの対照に最も興味をそそられます。職場のグループで意思決定を行うとき、特定の種類の求職者を雇うなど、強い偏見を持つ個人に遭遇することがよくあります。するとき、私たちには選択肢があります。私たちは、物事を公平に保つために、スキージャンプの審査員のように行動し、偏見に抵抗することができます。または、フィギュアスケートの裁判官のように行動して、「この男をジョーに雇うことは本当に重要だと思うので、私が一緒に行けば、彼は私に何を返すのだろうか」と言うことができます。私たちはおそらく、私たちの生活の中で両方の例を見てきたでしょう。

同僚から「スキージャンプ」または「フィギュアスケート」のどちらの行動をとるかは、何によって決まりますか?インセンティブはストーリーの一部であり、組織文化はそれらのインセンティブの作成に役立ちます。有能な投票トレーダーが精通したオペレーターと見なされるか、組織の使命を損なう誰かと見なされるかは、部分的に価値の問題です。しかし、文化は人々が直面するインセンティブの産物でもあります。「熟練したオペレーター」が世界で上に上がるかどうかは、そのスキルが尊重される程度に影響します。

エコノミストとして、フィギュアスケートの審査員のインセンティブを修正する方法を知っています。文化の修正はより困難ですが、私の希望は、インセンティブを正しく得ることができれば、文化が最終的に続くことです。

How ski jumping gets Olympic judging right (and figure skating gets it wrong)

Some amount of bias is probably inevitable in judged sports. The question is, can a sport do anything to control it? As an otherwise serious academic economist, I got interested in Olympic judging because I was interested in how groups of people make decisions. A group of judges picking a gold medalist is at least a little analogous to a committee deciding whom to hire. Individual members each have their own opinions about the decision, and these opinions reflect both valuable information and the members’ biases. The question is how to combine these opinions, and how to create incentives for members to stay as unbiased as possible.

Both ski jumping and figure skating have nationalistic judging biases, where judges give higher scores to athletes from their countries. But the sports take very different approaches to dealing with this. Ski jumping has its international federation select the judges for competitions like the Olympics, and I find that they select the least biased judges. Figure skating lets its national federations select the judges, and my research showed that they select the most biased judges.

This creates different incentives for judges. Ski jumping judges display less nationalism in lower-level competitions — it appears they keep their nationalism under wraps in less important contests to avoid missing their chance at judging the Olympics. Figure skating judges are actually more biased in the lesser contests; they may actually be more biased than they would like to be due to pressure from their federations.

Despite being nationalistically biased, ski jumping judges appear to care about fairness. Having a compatriot judge is actually not an advantage in ski jumping. I find that while you get a higher score from your compatriot, the other four judges lower your score ever so slightly, leaving you no better (or worse) off.

The reverse happens in figure skating. Not only does a figure skater with a compatriot judge get a higher score from that judge, but they also get higher scores on average from the other judges, too (compared with events when they are not represented on the panel). This is evidence of vote trading, of the kind that occurred at the Olympics in 1998, 2002, and (allegedly) is occurring in 2014. Most of the benefit of having a compatriot judge actually comes through the vote trading. Skaters even benefit from having compatriot judges on the panels of other events, which is consistent with the fact that the vote trading we know about is often across events.

The dysfunctionality of the sport is also revealed by how it reacted to the 2002 judging scandal. The International Skating Union made a couple of sensible reforms, such as increasing the size of the judging panel (at least temporarily) and making the scoring system more objective (although some think they went too far). But most of their response consisted of hiding the evidence of bias. The ISU stopped revealing which judge gave which score, making it much harder for competitors and fans to see whether the judging was fair. The ISU even went back and altered online score sheets from earlier competitions, obfuscating which judge gave which score and even which country each judge represented. They also began randomly dropping scores from three out of 12 judges. As any statistician can tell you, an average of nine out of 12 scores is essentially the average of the 12 scores plus a random number. When Yale statistics professor Jay Emerson noticed that in one case this randomness had altered who won a medal, it appears that the ISU responded by scrambling the order that scores were reported on score sheets. The only plausible purpose of this change was to make it harder to identify cases where randomness had affected results. All this suggests that the focus has been on hiding problems rather than fixing them.

While the scrubbing of past score sheets and randomization are very hard to defend, the ISU argues that judge anonymity should actually help prevent vote trading deals by making it easier for judges to secretly renege on them. The argument is basically the same for the secret ballot in elections or voice voting in legislatures, where the idea is to protect voters or lawmakers from external influences. Anonymity, though, also protects judges from monitoring by outsiders. I find that judging biases got about 20 percent larger after anonymity was introduced, suggesting that in this case, transparency is the better approach.

Of all these results, I am most intrigued by the contrast between the ski jumping judges undoing each other’s biases and the figure skating judges reinforcing them. When we make decisions in a group at work, we often encounter individuals with strong biases — say to hire a particular type of job candidate. When we do, we have a choice. We can act like a ski jumping judge, and resist the bias, in an effort to keep things fair. Or we can act like a figure skating judge and say “hiring this guy really seems important to Joe, I wonder what he’ll give me in return if I go along.” We have probably all seen examples of both in our lives.

What determines whether we get “ski jumping” or “figure skating” behavior out of our colleagues? Incentives are part of the story, and an organizational culture helps create those incentives. Whether a skilled vote trader is viewed as a savvy operator, or as someone who undermines the organization’s mission, is partly a question of values. But culture is also a product of the incentives people face. Whether the “skilled operators” move up in the world affects the extent to which that skill is respected.

As an economist, I know how to fix figure skating judges’ incentives. Fixing culture is harder, but my hope would be that if you can get the incentives right, the culture will eventually follow.

BuzzFeed News(2)フィギュアスケート審査員がオリンピック表彰台をどのように形作ったか

https://www.buzzfeed.com/johntemplon/by-voting-for-their-own-figure-skating-judges-may-have

自動翻訳(原文は下にあります)

2018年冬季オリンピックでの2週間のフィギュアスケートは、ファンにタイトなスピン、緊密な競争をもたらし、ジャッジは自国のスケーターを好む傾向を示し続けました。

オリンピックの前に、BuzzFeed Newsの調査により、裁判官は一貫して自国のスケーターのスコアを押し上げていることがわかりました。新たな分析によると、今年のオリンピックでは、少なくとも2つのケースで、国家の選好の可能性が最終順位に影響を与えた可能性があります。

フィギュアスケート競技が終了した今、韓国の250のすべての公演の数値を計算し、オリンピック審査員の母国の選好が以前の評価をわずかに上回っていることを発見しました。2016年10月から2017年12月の間に17のハイレベルな競技会を検討したところ、3.4ポイントの上昇がありました。これらのゲームでは、その数字は3.9に上昇しました。

それでも、このパターンは、誰が金メダルを家に持ち帰るかに影響を与えるほど結果的かもしれません。アイスダンスコンテストでは、カナダのテッサバーチューとスコットモワールのライバル、フランスのガブリエラパパダキス、ギヨームシゼロンを超えて、自国の好みが勝者を押し上げたようです。

2つのアイスダンスペアは、オリンピックに向かうお気に入りの1つでした。カナダ人は、最終順位でわずか0.79ポイントだけフランスを負かしました。

しかし、カナダ人にも利点があったかもしれません:審査員団。

スケートカナダの社長である Leanna Caron は、アイスダンスコンペティションの両方のプログラムを審査するために選ばれました。(9人の審査員が、競技の各セグメントの前に13のプールからランダムに選択されます。)両方の 時間で、彼女は、パネルの他の審査員の平均よりも高いスコアをバーチューとモアに与えました。

「審査員の選出には関与していません。どの国がパネルに座るかは関係ありません」とロイターは記者会見で語った。

「スケートカナダでは、非常に公正なプロの審査の歴史があり、それを誇りに思っています。カナダ人として、あなたがオリンピックで勝つとき、それはあなたがそれに値するときであり、私たちはこれらのオリンピックメダルのように感じます。

BuzzFeed Newsは、フランスとカナダの裁判官のスコアが単純に削除された場合にどうなるかを計算しました。そのシナリオでは、ショートダンスパネルには7人の裁判官しかいなかったでしょうし、フリーダンスパネルには8人の裁判官しかいなかったでしょう。この分析でも、パパダキスとシゼロンは、この場合0.46ポイントだけ、金メダルの美徳とモアを通過したでしょう。

中国のジン・ボヤンは、男子コンペティションに参加する可能性のある別のメダルと考えられていました。そして、中国の裁判官の一人は、同様に非常に高い本国の選好を示しました。

裁判官のWeiguang Chenは、ショートプログラムの期間中に同国人のジンに平均より10.7ポイント上回った。フリースケート中、チェンはジンを平均よりも25.0ポイント高く評価しました。これは、オリンピック全体のフィギュアスケートジャッジによる最大のブーストです。

An analysis by BuzzFeed News shows that judges displayed a strong preference for skaters from the same country at the 2018 Winter Olympics, and that it may have made a difference in a gold medal finish.

Two weeks of figure skating at the 2018 Winter Olympics provided fans with tight spins, close competitions, and judges continuing to show a preference for skaters from their own country.

Before the Olympics, a BuzzFeed News investigation found that judges consistently boost the scores of skaters from their home country. A new analysis shows that in this year’s Olympic Games, possible instances of national preference may have affected the final standings in at least two cases.

Now that the figure skating competition has concluded, we’ve crunched the numbers for all 250 performances in South Korea and found that home-country preference of Olympic judges slightly outpaced our earlier assessment. When we examined 17 high-level competitions between October 2016 and December 2017, there was a bump of 3.4 points. In these games, that figure climbed to 3.9.

The two ice dancing pairs were among the favorites heading into the Olympics — and the Canadians bested the French by just 0.79 points in the final standings.

But the Canadians may also have had an advantage: the judging panel.

Leanna Caron, the president of Skate Canada, was selected to judge both programs in the ice dance competition. (Nine judges are randomly selected from a pool of 13 before each segment of the competition.) Both times she gave Virtue and Moir a score that was higher than the average of the other judges on the panel.

And both times, she scored the French team lower than any other judge.

In an email, a spokesperson for Skate Canada declined to respond about the scores of its judges, but told BuzzFeed News that “all of the Canadian judges submitted to the ISU for the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games meet the eligibility criteria, and were approved as judges by the ISU, according to its rules and regulations.”

Christine Hurth, France’s ice dance judge at the Olympics, was only selected to score the short dance, which made up about 40% of each team’s total. Hurth gave the Canadian team the lowest score of any judge for the short dance. She scored the French about average.

The French skating federation did not respond to phone calls and emails requesting comment.

After the competition, BuzzFeed News calculated what would have happened if the Canadian and French judges’ scores were all replaced by those of an “average” judge. In that scenario, Papadakis and Cizeron would have won the gold medal by 0.39 points. (You can read more about our analysis here.)

“We aren’t involved in the picking of the judges, we’re not concerned with what country sits on the panel,” Moir told a news conference, according to Reuters.

“At Skate Canada, we have a history of very professional judging that’s very fair, and we’re proud of that. I feel that, as Canadians, when you win in [the] Olympics, it’s when you deserve it, and we feel like these Olympics medals, that we deserve [them].”

BuzzFeed News also calculated what would have happened if the scores of the French and Canadian judges were simply removed. In that scenario, there would have been only seven judges on the short dance panel and only eight judges on the free dance panel. In this analysis, too, Papadakis and Cizeron would have passed Virtue and Moir for the gold medal, in this case by 0.46 points.

China’s Jin Boyang was considered another medal hopeful entering the men’s competition — and one of the Chinese judges displayed a remarkably high home-country preference as well.

The judge, Weiguang Chen, scored her countryman Jin a total of 10.7 points above the average during the short program. During the free skate, Chen graded Jin a whopping 25.0 points above the average — the biggest boost by any figure skating judge during the entire Olympics.

Figure skating's scoring system reduces the effect of extreme judgments by throwing out the highest and lowest score for each part of a performance. But very high scores can still influence the outcome by preventing the next-highest score for each part from being discarded.

The Chinese skating federation and Chen did not respond to phone calls or emails requesting comment.

Jin ultimately finished fourth, in front of American Nathan Chen by just 0.42 points. The American had his own home-country judge on the panel. Even so, if the scores for both the Chinese and American home-country judges were replaced with those of an “average” one, the American skater would have finished fourth — ahead of Jin.

The ISU is responsible for monitoring judges. But our previous investigation showed that its own system for catching outliers very rarely flags their scores. The system would have flagged both times Chen judged Jin during the men’s competition.

And finally, Lorrie Parker, the American judge, stood out by giving US skaters three of the biggest home-country boosts. She scored Americans Adam Rippon and Nathan Chen 11.6 and 11.5 points above the average, respectively, during the free skate of the men’s competition. Her grade of Rippon during the men’s free skate in the team event was 10.9 points above the average.

The US Figure Skating Association and Parker did not respond to emails or phone calls for comment.

BuzzFeed News(1) ナショナルバイアスとオリンピック

この記事は、自動翻訳されたものです。本文は翻訳文の下にあります。原文へのリンクはこちらです→https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/johntemplon/the-edge

※羽生選手ファンのSIENNAさんがご自分のブログで詳しく翻訳されています。自動翻訳よりわかりやすいです。→https://ameblo.jp/sienna12/entry-12387355733.html

トップレベルのフィギュアスケート審判員は、常に自国のスケーターを支持しています。今、それらの裁判官の多くはオリンピックにいます。

スポーツのトップレベルでは、ジャッジは自国のフィギュアスケーターに高い評価を与えます。BuzzFeedNewsのデータ分析によると、場合によっては最終結果に影響します。そして、自国のスケーターを最も一貫して後押しした16人の審査員が今週平昌に来て、オリンピックの歴史を決定します。 今週、世界のトップスケーターが韓国に集結し、オリンピックの栄光に向けてジャンプ、スピン、ツイストを繰り広げる中、彼らの成功を決定する要因はトリプルアクセルだけではないかもしれません。BuzzFeed Newsの調査によると、スポーツの最高レベルでは、多くの場合、ジャッジの母国に有利になるように得点が傾いています。 3人の著名な統計学者と協議して開発された排他的な分析で、BuzzFeed Newsは1年以上の得点データを計算し、自国のスケーターを後押しする裁判官がスポーツにあふれていることを発見しました。集合的に、米国やロシアなどのスポーツの大国の審査員は、一貫して自分のスケーターをアップスコアしました。韓国の冬季オリンピックの48人の審査員のうち16人は、自国の好みのパターンを示しているため、偶然に発生する確率は100,000分の1未満です。これらの裁判官には、ロシアから送られた3人すべて、中国から3人、カナダと米国から2人ずつが含まれます。 本国の選好は長い間噂されてきましたが、BuzzFeed Newsの統計分析は初めて、本国の選好がスポーツを苦しめているという圧倒的な証拠を提供します。分析によると、1人のジャッジの得点によって、最終的なランキングでのスケーターの立場に違いが生じる可能性があります。 ナショナルバイアスの明確な傾向が見られます」と、ロイヤルダッチスケート協会は昨年秋に宣言しました。 提案を作成したオランダの裁判官Jeroen Prins氏は、国内のバイアスは「十分にチェックされていない」と述べた。「多くの人が懸念を共有していると思います。なぜなら、私たちは審査されたスポーツにおいて信頼性が必要だからです。 高いホームカントリースコアはそれ自体ではなく、裁判官が意図的に同胞の地位を上げようとしていることを示しています。スコアは、たとえば、地域のスタイルのスケートの好み、またはジャッジが特別な注意を払ったスケーターに対する傾向、または単に愛国心さえ反映している可能性があります。裁判官は、彼らが一貫して彼らの同胞をアップスコアしたことに気づかないかもしれません。そして、BuzzFeed Newsと話をしたスケート関係者の大多数は、審査のスキャンダルがISUに行動を促す2002年のソルトレークシティ冬季オリンピック以来、審査の質が向上したと述べました。 しかし、システムには大きな問題が組み込まれたままであり、現在および以前の役人は次のように述べた。各国のスケートプログラムは独自の裁判官を選ぶ。米国フィギュアスケート協会はオリンピックに出場するアメリカの裁判官を選択し、ロシア協会はロシアの裁判官などを選択します。当局によると、このプロセスはバイアスに対するインセンティブを生み出す:全国連盟は、スケーターに最高のスコアを与えるジャッジを求めている。ジャッジが「好きではないことをすれば、彼らの国は彼らを削除して別のジャッジを任命するだけだ」と、元米国国民レベルのスケーターであるティム・ガーバーは語った。 ISUは、BuzzFeed Newsの分析についてコメントすることも、組織が裁判官をどのように評価し、規律するかについての詳細な質問に答えることを拒否しました。では簡単な声明、ISUは、それが「密接にすべてのISUフィギュアスケートイベントの判定を監視し、場所で堅牢な評価および報告の手順を持っている。」と述べました さらに、「ミスを犯したり、スケーターをマークしすぎているジャッジは警告を受け、ISUによってペナルティを受ける可能性がある」と付け加えた。現役人によると、今シーズン、ISUは審査員を評価する際に「バイアス」を探すよう役人に求めた。 ISUの手順の重要な要素の1つは、スコアが「廊下」と呼ばれるものの外側にあるジャッジにフラグを付けるアルゴリズムです。つまり、パネル上の他のスコアの平均を上回るまたは下回るバッファゾーンです。しかし、裁判官を監督し、彼らを制裁するかどうかを決定することを任務とする2人の元高レベルISU職員は、BuzzFeed Newsに、廊下が非常に幅が広く、極端な異常値のみを捕らえたため、アルゴリズムは無効であると語った。この主張をテストするために、BuzzFeed NewsはISUのアルゴリズムを再作成し、スコアにフラグを立てることはほとんどないことを発見しました。 さらに、ISUのシステムは一度に1つのパフォーマンスのみを監視します。結果として、多くの公演で一貫してホームカントリーのスケーターにささやかな後押しを与える審査員は検出されません。 2011年にイタリアの裁判官が同僚の得点を記録しているように見えるビデオで逮捕されたときのような重大な場合を除いて、ISUは伝えた警告や制裁を公表しません。ISUは、BuzzFeed Newsが自国のスケーターを他のジャッジの平均スコアより上にマークする一貫したパターンを示していると判断したジャッジのバイアスを認めていないことを知っています。 何十年にもわたって組織に勤務してきた6人の元トップレベルISU職員は、裁判官の出身国の選好を管理することは常に課題であると認めていました。「この問題を解決しないと、元ISU高官の1人は、「手に負えなくなる可能性があります」と述べました。 「誰もが自分の国を表彰台に見たいと思っています」と、国際的な裁判官を監視する委員会の元メンバーを追加しました。「私が裁判官だったとき、私はスケーターを1つ上の位置に配置していました。」 ISUは10年以上にわたって、どの審査員に授与されたかを特定せずにスコアをリストしました。しかし、それは、2016年から17年のシーズンの初めに変化し、ISUは、ジャッジがそれぞれのスコアを与えたリストの以前の慣行に戻った。ISUは声明の中で、「匿名性の取り消し」は、「審査の質だけでなく、バイアスも追跡することを可能にします」と述べました。 変更が実施されたときから2017年12月までのすべての主要な国際大会からすべてのスコアリングデータを収集しました。審査員のスコアとそのパネルの他の審査員によって与えられたスコアの平均との差を調べました。(分析の詳細については、こちらをご覧ください。) すべての裁判官が母国のスケーターを好むパターンを示したわけではありません。しかし、分析では、スポーツ全体で、国家主義的な選好が一般的であることが示されました。1,600を超えるパフォーマンスで、平均してフィギュアスケートの審査員は、ホームカントリーのスケーターに3.4ポイントのアドバンテージを与えました。これは、プログラムによっては、最終オリンピックの最終スコアが40から220以上に及ぶスポーツの合計スコアのわずかな割合です。しかし、このような小さな違いでも最終結果が変わる可能性があることがわかりました。 スケート競技では、男子、女子、ペア、アイスダンスなど、すべての国での選好が見つかりました。この現象は、スポーツを支配している国で特に顕著です。中国の裁判官は平均して、中国のスケーターに4.6ポイントの上昇を与えました。これは、分析されたデータセットBuzzFeed Newsで少なくとも50の自国の判断を持つ国の中で最大です。イタリア、ロシア、アメリカ、カナダはすべて、スケーターに3.4ポイント以上のブーストを与えました。 統計分析では、審査員の技術的な熟練度や、特定のパフォーマンスに対する正しいスコアがどれくらいかを判断することはできません。その代わり、私たちのアルゴリズムは、同じパフォーマンスを司る他のジャッジの平均よりも、ジャッジが一貫して自国のスケーターを採点するかどうかを明らかにします。 私たちは意図的に非常に高い水準を設定しました:リストに掲載するために、個々の裁判官は、ホームカントリーのスケーターをマークする一貫した明確なパターンを示さなければなりませんでした。偶然に発生した確率は100,000分の1未満でした。つまり、同胞を数回しか採点しなかったジャッジは、たとえそのたびにそれぞれの国のスケーターを強く支持していても、現れないかもしれません。 もちろん、統計だけでは、裁判官が同胞に高いスコアを与えた理由を説明することはできません。現在の裁判官および元裁判官とのインタビューによると、多くの要因が関与している可能性があります。文化の違いにより、裁判官は世界の彼または彼女の地域で一般的なスケートのスタイルを好む傾向があります。ジャッジは自国のスケーターをよく知っており、彼らがスポーツで成長し、全国大会で頻繁にジャッジし、彼らのルーティンに慣れる-ジャッジがスコアを上げるのにつながるすべての要因。前の関係者によると、一部の裁判官は、自国のスケーターが「朝食を食べた」ことを知っています。 ジャッジは、彼らがスポーツで成長するのを見て、母国のスケーターをよく知っています。 しかし、より多くの不吉な力も働く可能性があります。少なくとも3人の現ISUおよび元ISU当局者は、裁判官が時々共謀して特定の国を下院し、他の国を上院に送ると述べた。コーチと裁判官は、しばしば彼らの国からのスケーターのために、時には微妙に、時には露骨にロビー活動をします、とこれらの当局者は言いました。また、場合によっては、特定のスケーターの得点はほとんど事前に決められていると彼らは言いました。 「5〜6人が、自分がやろうとしていること、マークする範囲、チームの後を追う方法に同意しているパネルにいることがあります」と別の審査員は説明しました。そのような場合、彼女は、その共謀に参加せず、したがってスコアがパネル上の他の人と一致しない人は、「実際にはそうではないが、偏っているように見える」と述べた。 これらの27人の裁判官は10か国にまたがっています。国際審査員としてキャリアを始めて数年しかいない人もいれば、何十年もそれに取り組んできた人もいます。 この27人の審査員のうち、16人が平昌のオリンピックに選ばれました。(上記のチャートを参照してください。) BuzzFeed Newsは、27人の審査員全員に国内の連盟を通じてコメントを求めたほか、電話、電子メール、Facebook、または職場で残されたメッセージによって審査員自身に連絡しました。米国と中国のスケート連盟はコメントを避けた。 Skate Canadaの広報担当者はメールで、BuzzFeed Newsに次のように語っています。 」ロシアのフィギュアスケート連盟の代表者は質問に答えることを拒否し、「私たちの裁判官は誰もコメントしたくない」と言った。 ほとんどの審査員は、メッセージに応答しなかったか、記録上で発言しないことを選択しました。平昌五輪にコメントした唯一の裁判官は、イタリアのウォルター・トイゴだった。Toigoは無関係な問題で2年間中断されました。彼は明らかに別の裁判官のマークをコピーしているように見えました。しかし、私たちの分析では、彼は別の理由で際立っていました。彼は母国のスケーターに平均7.5ポイントのアドバンテージを与えました。これは私たちのリストに載っているオフィシャルの中で最大です。「誰もが異なる意見を持っているので、私たちが見ることができるものを判断します」とToigoはBuzzFeed Newsに語った。「私たちは人間であり、機械ではありません。私が思うに判断します。すべてのスケーターと一貫性を保つよう努めています。」 Toigoの停止(彼は「同意しなかった」と彼が言った)を除いて、ISUは27人の裁判官のいずれも公的に認可していません。 ISUは、ソルトレークシティオリンピックでの投票取引計画が公のスキャンダルになった2002年に、その信頼性に打撃を受けました。それに応じて、ISUは審査システムを全面的に見直しました。 To make scoring less subjective, the ISU put more emphasis on the technical elements of a program. Formerly, judges awarded competitors just two scores on a scale of 0 to 6.0; now, judges evaluate each jump, spin, or step sequence individually on a scale from –3 to +3, which is then adjusted for difficulty. They also grade five different artistic components of the program. A skater’s final score is a complex calculation based on the scale of difficulty of the program and an average of the judging panel’s marks. The highest and lowest scores for each aspect are tossed out to lessen the influence of outliers. Since the 2002 scandal and the introduction of the new judging system, the sport has been largely cleaned up, said Charles Cyr, the ISU’s sports director for figure skating. “It’s a new breed of judges. Let me tell you they’re not wilted lilies,” he said. “The old guard of judges from 15 or 20 years ago have retired and gone,” he added, taking with them “the old adage of ‘I have to do what my country says.’” “I heard judge after judge going up to the microphone and say, ‘I want to be accountable for my marks. The good judges have nothing to hide.’” “Anonymous judging was the worst mistake ever made by the ISU,” said Sonia Bianchetti, an ISU hall of famer who used to serve as a judge and technical committee chair. The change made it almost impossible to see if judges were making errors or regularly scoring their own skaters higher, she said. It was a stark change from the 1970s, when she led the successful effort to suspend all Soviet judges for an entire season because they had demonstrated repeated national bias. When the Russian skater Adelina Sotnikova beat out Korea’s Yuna Kim for the women’s gold medal at the Sochi Olympics in 2014, one of the Russian judges sparked an uproar when she was seen hugging Sotnikova backstage after the win. The Korean skating federation accused the Russian federation of an ethics violation for appointing that judge, who was married to the former head of the Russian skating federation. The ISU dismissed the complaint. Two years later, at the 2016 ISU Congress in Dubrovnik, Croatia, skating federations voted almost unanimously to end anonymous judging. “I heard judge after judge going up to the microphone and say, ‘I want to be accountable for my marks,’” said John Coughlin, a 2012 US national champion who currently serves on one of the ISU’s technical committees. “The good judges have nothing to hide.”Matthew Stockman / Getty Images Mirai Nagasu competes in the women's short program during the 2018 Prudential US Figure Skating Championships at the SAP Center on Jan. 3 in San Jose, California “Almost impossible to get flagged” The ISU has its own algorithm for catching scoring errors or potential bias — but some insiders say it is not effective. “The corridor is so big that it’s almost impossible to get flagged,” said a former ISU technical committee member. “The judges really know how do it — how to play within that band,” said another former ISU technical committee member. “It’s quite a huge margin that the ISU allows,” said a former high-level member of a national federation. To see if these claims were valid, BuzzFeed News recreated the ISU system that highlights scores far above or below the average — or outside the corridor, in skating parlance. Public ISU documents describe the system in detail, and BuzzFeed News translated that description into a computer algorithm. We consulted with Prins, the Dutch judge, and academic literature to verify our interpretation. We also shared a draft of our methodology with the ISU, which declined to confirm or correct it. We found that the ISU’s system would have flagged barely 1% of all scores for technical elements and an even smaller fraction of scores for artistic components. Unlike our analysis, the ISU’s system only looks at one performance at a time, flagging any scores that fall far enough from the average. So if, during a particular competition, one judge gave a skater from her home country a much higher score than any of the other judges on the panel, the algorithm would detect that anomaly, and members of the technical committee would follow up to determine if the outlying score was the result of error or bias. But the algorithm does not track patterns across time. So it wouldn’t flag a judge who consistently gave skaters from her home country a less noticeable boost across many different performances or even many years. A review of the ISU’s online disciplinary records shows that there have been no major punitive actions over the last decade explicitly related to judges scoring their home countries’ skaters higher. However, the ISU does not release information when a judge receives more minor sanctions — such as a “letter of criticism” or an “assessment.” Cyr defended the ISU’s decision to keep these evaluations private, comparing them to a company’s internal disciplinary records of its employees, but other current officials said greater transparency would improve the sport. “If the ISU did make these people public, they’d get better,” said one former high-level ISU official. After the 2014–15 season, the ISU stopped publishing even the total number of assessments it hands down. Within the ISU, responsibility for evaluating judges falls mainly to two technical committees, each a panel of three international judges, an athlete, a coach, and a chairperson. These committees wield considerable power: Not only can they recommend sanctioning a judge, but they can also set new rules in the sport and determine the list of qualified judges for each season. At every international competition, referees help oversee judges. Referees score each skating performance independently from the judges, and they can recommend that a technical committee give additional scrutiny to a judge. “They’re not policing it,” said a former skating official. “It’s all a bit farcical.” High-level ISU events, such as the World Championships or the Olympics, include an extra layer of oversight for judges. A pair of observers, known as an Officials Assessment Commission, reviews any outlier scores flagged by the ISU’s algorithm. The technical committee can then recommend a letter of criticism or assessment to the judge. That recommendation must be approved by the sports director. Repeated assessments can lead to a suspension or a demotion. Some officials said that the system for overseeing judges had enough checks and balances to protect the integrity of competitions. “The judges know that even though the event is done, their marks are going to be scrutinized,” the ISU’s Cyr said. But others officials refuted that claim. In interviews, officials said they couldn’t recall a judge who the ISU had booted out for good. “They’re not policing it,” said a former skating federation official. “It’s all a bit farcical.” Our analysis shows that just one judge can influence the final results. One example: At the men's competition at the Progressive Skate America in October 2016, Russian judge Maira Abasova scored her compatriot Sergei Voronov higher than any judge except for one. Abasova’s score helped boost Voronov into fourth place overall, just 0.20 points ahead of Boyang Jin, a Chinese skater, in the final standings. It’s impossible to know why Abasova gave the scores she did, but replacing her marks with the average of the other judges would have dropped Voronov into fifth — behind Jin. Abasova could not be reached, but BuzzFeed News sent a letter with detailed questions to her through the Figure Skating Federation of Russia. A federation representative declined to comment or make the judge available for an interview but said, “Abasova is aware of the letter and has no comment.” A former high-level ISU official said that it was common to push one’s own skaters, explaining, “If you don’t do it, if you don’t join in the game, then you get left behind.” ●

羽生結弦選手の技術と芸術性を評価した論説あれこれ

羽生結弦選手の芸術性について、異分野の知識や見識を持った方々の

論評をご紹介します。

フィギュアライターと言われる方々からは得られない

高度で深い内容になっています。

◆羽生選手の芸術的卓越性について書かれたもの

◇太田龍子さんのエッセイ

鬼たちに捧ぐ 羽生結弦に幽玄を見た日

https://ncode.syosetu.com/n4449fy/

羽生結弦ー「秋によせて」に修羅を想う

https://ncode.syosetu.com/n6779fy/

能とフィギュアスケート、技術と表現について思うこと

https://ncode.syosetu.com/n9778ga/

◇yosiepen’s journalさん

www.yoshiepen.net

使命感、それに揺るぎない自信がみなぎっていた羽生結弦選手の「SEIMEI」in 「四大陸フィギュアスケート選手権2020」@ソウル 2月9日 - yoshiepen’s journal

受肉した青い炎−−羽生結弦選手の「バラード第一番」in「フィギュアスケート四大陸選手権男子SP」@ソウル2月7日 - yoshiepen’s journal

この他、ブログの右側にあるカテゴリー欄で羽生結弦を選んで

クリックすると90項目の記事が見れるようです。

◇菅沼伊万里さん

ダンスのプロが分析する、羽生結弦選手の表現と魅力

「スポーツ競技」から飛び出した唯一無二の「芸術作品」

precious.jp

◆羽生選手の技術的卓越性について書かれたもの

◇高山 真「羽生結弦は捧げていく」連載シリーズ

羽生選手の凄さを技術面から詳細に論評したエッセイ集「羽生結弦は助走をしない」の番外編。

shinsho-plus.shueisha.co.jp

◇惑星ハニューにようこそ(ミラノ在住さんのブログより)

羽生選手ファンにはおなじみのイタリアの冬季スポーツの解説者として有名な

マッシミリアーノ・アンべージさんのポッド・キャスト「みんな羽生結弦にくびったけ」

をブログ主のミラノ在住さんが翻訳してくださっています。

羽生選手の技術面・芸術面について熱く語っています。

Neveitaliaポッドキャスト「みんな羽生結弦に首ったけ、競技を変革する男(その1)」 | 惑星ハニューにようこそ

Neveitaliaポッドキャスト「みんな羽生結弦に首ったけ、競技を変革する男(その2)」 | 惑星ハニューにようこそ

Neveitaliaポッドキャスト「みんな羽生結弦に首ったけ、競技を変革する男(その3)」 | 惑星ハニューにようこそ

Neveitaliaポッドキャスト「みんな羽生結弦に首ったけ、競技を変革する男(その4~最終回)」 | 惑星ハニューにようこそ

データは、フィギュアスケートの審査システムに偏りがあることを示していますか?

私はフィギュアスケートの大ファンです。このスポーツに関する私の話は2005年に始まり、ここ数年はそれをきちんとフォローしていませんでしたが、2018年のオリンピックではこれまでになかったほどスポーツに戻りました。インターネットやソーシャルメディアの時代には、すべてがより面白くなり、コンペを何度も見たり、技術的なことを簡単に学んだり、オンラインフィギュアスケートコミュニティに参加したりできます。最近、フィギュアスケートファンのコミュニティでは、UNFAIR JUDGING SYSTEMというトピックが常に話題になっています。

古くて新しいスケートファンは、ある特定のスケーターが絶えず強調されていることに気付きました。ISU(国際スケート連合)は過去に歴史的な腐敗を抱えており、オリンピック大会中の汚職スキャンダルのために、2002年に採点システムを変更する必要がありました。フィギュアスケートのファンは、2014年のソチオリンピックのキムユナ銀メダルとして、それと他のエピソードを忘れていませんでした。

データは何を示していますか?1人のスケーターが常にオーバースコアされているのは本当ですか?このスケーターに対して審査員は偏っていますか?

テクニカルスコアは、要素ベース値+ GOE(Great of execution)スコアの合計で、新しいシステムでは-5〜+5の範囲です。2018年から19年のシーズン以前は、GOEの範囲は-3から+3で、各要素の基本値も異なっていました。

フィギュアスケートの世界のバイアスに関するすべての質問に回答するために、私はPythonパンダを使用してWebスクレイピングを行い、すばらしいWebサイト「skatingscores.com」からデータを取得しました。Webサイトにはテーブルのみが含まれており、パンダでデータを簡単に抽出できます。

各要素GOE、合計スコア、競合のデータを次のように選択しました。

この分析のために、私は、2019年の世界ランキング上位10位にランクインしている、および/またはグランプリファイナル2019および/またはグランプリファイナル2018に分類されている10人のスケーターを選択しました。前にも言ったように、採点システムは2018年に変更されたため、過去2年間で良い結果が得られるスケーターを選択することが重要です。

10人のスケーターのうち6人は2019年グランプリファイナル(2019年12月)の6人のスケーターであり、彼らは羽生結弦(日本)、ネイサン・チェン(アメリカ)、ケビン・エイモス(フランス)、ドミトリ・アリエフ(ロシア)、アレクサンダー・サマリン(ロシア)です、ボヤンジン(中国)。

ジェイソン・ブラウン(米国)、2019年世界選手権のトップ9。Junhwan Cha(韓国)銅メダル2018–2019グランプリファイナル。宇野翔馬(日本)、2019年世界選手権で4位。

現在、表彰台の高いチャンスと直接競合するスケーターは多くありません。したがって、この研究目的のためには、10人のスケーターで十分です。

フィギュアスケートファンの間での主な問題は、膨らんだGOE(実行スコアが大きい)に関することです。そこでは、ジャッジが最終スコアよりも強力になり、その後、実行された要素のベース値に触れることができなくなります。

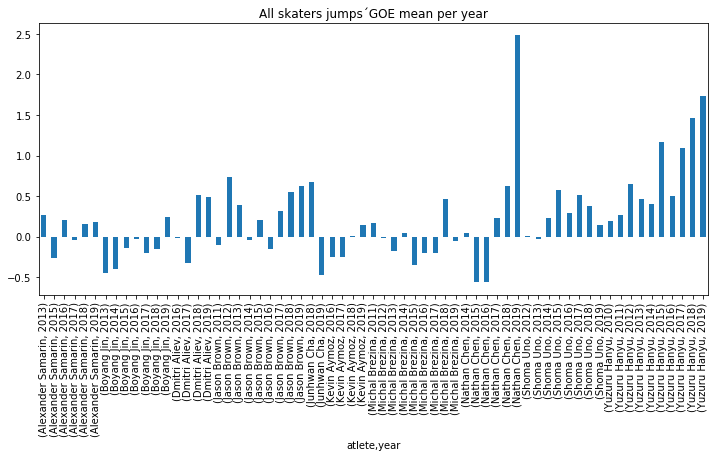

ジャンプは他の要素に比べてベース値のスコアが高いため、同じデータフレームでジャンプで受け取ったすべてのスケーターのGOEスコアをグループ化し、年間平均を計算してプロットします。

世界2018以降のGOE範囲スコアで-3 +3から-5 +5に変化があったため、ほとんどのスケーターが2017年から2018年にかけて平均GOEがわずかに増加したことは注目に値します。

ただし、Nathan ChenのジャンプGOEが2018年から2019年にかけて大幅に増加したことは容易にわかります。Nathanは、長年にわたって最高のGOE成長を示したスケーターです。彼は、2015年に最も高い負の平均GOEから始まり、2019年に他のどのスケーターよりもはるかに高い平均GOEを達成しました。

2018年から2019年にかけて、ネイサンチェンの平均ジャンプGOEは297%増加し、オリンピックチャンピオンの最高のGOE増加率の2回である羽生結弦は、2014年から2015年に185%増加しました。ドミトリ・アリエフとケビン・エイモスは、彼らのキャリアで一度だけ1000%以上の増加を示しましたが、それは彼らのシニアキャリアの始まりでした。

以下の画像には、年間10人のスケーターの増加率が含まれています。

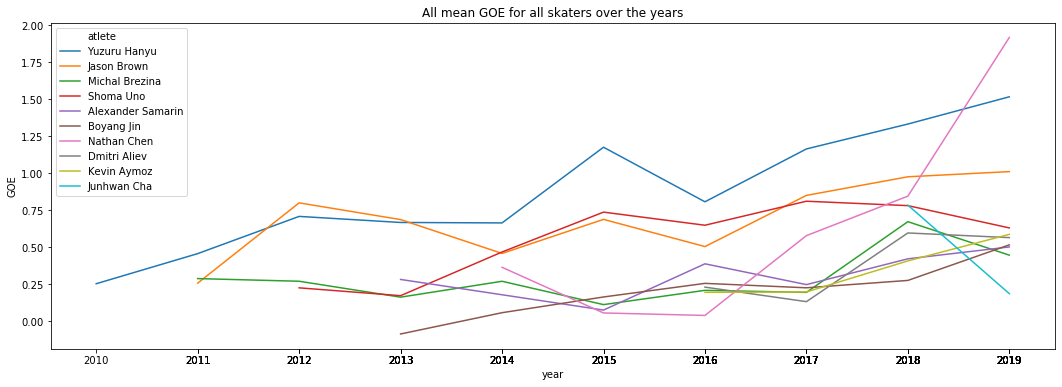

次の画像は、長年にわたるすべてのスケーターの平均ジャンプGOEです。Hanyu Yuzuruのピンクのドットは、2015年から2019年まで同じパターンの成長を示しました。一方、2018年から2019年まで、Nathan Chenは他の全員を置き去りにして、平均スコアがほぼ300%増加しました。ここでバイアスの可能性を確認できます。

ジャンプ以外; スピン、ステップシーケンス、振り付けもGOE評価を受けます。これらの要素の基本値はジャンプよりもはるかに低いため、同じデータフレームにグループ化しました。

ジャンプグラフとは異なり、ここではジェイソンブラウンの高得点が表示されます。彼は高品質のスケートスキルを持つ非常に芸術的なスケーターとして知られています。目に見えるのは、これらの要素がほとんどのスケーターの時間とともに少しずつ成長することです。2014年から2015年および2011年から2012年のジェイソン・ブラウンを除く。2010年から2011年および2014年から2015年の羽生結弦。2013年から2014年のボヤン・ジン。2018年から2019年のケビン・エイモス。2017年から2018年のミカル・ブレジナ。 2016年から2017年および2018年から2019年。

次の画像には、長年の10人のスケーターのジャンプ+スピン+コレオ+ステップシーケンスGOEスコアが含まれています

データがパターンを破ったときに、Nathan Chenが1年から別の年にどのように通常から大きく増加したかを簡単に確認できます。可能なこのグラフは、偏ったGOEスコアを示しています。この仮定を確認するには、さらに調査が必要です。この問題について、もう少し研究が近々行われることを期待しています。

フィギュアスケート選手のスコアが1年から別の年に大きく増加する可能性は本当にありますか?上のグラフを参照してください。NathanChenのすべてのシニア年からのジャンプの平均散布図とspins_step_choreoの平均散布図の散布図です。ドットの1つは、ある年から別の年まで、他のドットから離れすぎています。

次のグラフは、すべてのスケーターがGOEを意味することを考慮した散布図です

スコアリングシステムは2018年に変更されたため、GOEスコアの進行をグラフで表示し、データを3つに分割した分布を見てみましょう:2018、2019-2019 GPF(Grand Prix Final)、および2019 GPF。

すべてのスケーターを考慮すると、3つのケースの分布は非常に似ています。採点システムは2017年から18シーズンの最後の競技後に変更されたため、2018年まではいくつかの競技がまだ古い採点システムを適用していました。これは、2018年と他の2つのデータの違いを説明しています。

さて、2019年の最後の大会の3人のメダリストの注文を順番に見てみましょう:ネイサン・チェン、羽生結弦、ケビン・エイモス。

Nathan ChenとKevin Aymozが過去2シーズンに比べて良い結果を得たことがわかります。一方、羽生結弦の得点は、その時点での2019-20シーズンの得点と比較して、決勝で低かった。

結論:

データ可視化により、ネイサンチェンGOEsスコアが短時間で大幅に増加したことを確認できます。これは、スケーターがそのような増加を提示する前に、オリンピックチャンピオンの2回と2018年のオリンピック銀メダリストを含む、現在競合しているトップ10のフィギュアスケート選手の間でGOEスコアで。特に2018年から2019年にかけて、Nathan Chen GOEスコアは、バイアススコアリングの可能性を示す赤信号を出します。

この問題に関するさらなる研究が必要です。フィギュア愛好家がフィギュアスケートデータセットの分析を行い、機械学習アルゴリズムを実装し、結果を共有することを望みます。

質問は次のとおりです。ISUは、1人のスケーターがこのような高いGOEを獲得することについて何か言うことができますか?フィギュアスケートのスキルの開発には時間がかかることが知られていますが、スケーターは1年から別の年に自然にこのような速いGOE成長を示すことができますか?

あなたの意見は何ですか?このトピックおよび/またはデータ分析についてのあなたの意見を知りたいです:)

確かなことの1つは、ISUがスケーターの得点を上げるためのテクノロジーを実装することです。現在、審査員は、実行されている要素をよりよく見るために、すべての角度でビデオを持っていません。また、今年、日本では、彼らはジャンプの高さ、氷の範囲、速度を測定できる技術を作成しました。IAは、ビデオに関する推論を行うことができる機械学習アルゴリズムでさらに役立ちます。

ISUがテクノロジーを使用してスケーターのパフォーマンスをよりよく評価することに同意する場合は、以下の請願書に署名してください。すべてのスケーターの正義のために何かを行う必要があります。

https://www.gopetition.com/petitions/figure-skating-to-improve-judging-system.html

参考データリンク先(2020.5.15追記あり)

参考データリンク先

基本的に羽生選手のファンブログは外してあります。

RinkResultsさん

選手、ジャッジ、所属クラブ、会場ごとにデータが検索できます。

いつもお世話になっている凄いサイトさんです。

こちらもデータの充実がすごい!

いつもお世話になっています。

(新)SkatingScoresさん

フィギュアスケート男女シングルの試合結果・ランキング・採点方法

https://figureskating.tororinnao.info/

フィギュアスケ―ティングチャートさん

メニューより、男女別、ジャンプ/スピン/ステップ別、スケーター別などで様々なデータを表示できるようになっています。

https://figure-skating-charts.com/

(新)フィギュアスケートジャッジスコアデータベースさん

年度別、試合別、個人別の成績が検索できます。

プロトコルが網羅されているのがありがたいです。

(新)フィギュア要素検索さん

誰がいつどんな要素を決めたかなどを調べることができます。

ガンディーのフィギュアスケート分析記録